NB: An earlier version of this post critiqued Victor Chernozhukov’s approach to directed a-cyclic graphs and fixed effects, but made some critical errors in interpreting his approach. These errors were entirely mine, and I apologize to Victor for doing so.

With the explosion of work in the causal analysis of panel data, we have an ever-increasing array of estimators and techniques for working with this form of observational data. Yiqing Xu’s new review article, available here, provides a remarkably lucid approach to understanding these new approaches. In this blog post I focus on some areas that I think are unclear in current panel data analysis in a causal perspective, especially fixed effects and the dimensions of variance in panel data. People familiar with my prior work will probably not be surprised at this; I believe that understanding these dimensions is critical to correct inference with panel data.

For those reading this post from disciplines outside the social sciences, or who are unfamiliar with this rapidly changing literature, panel data refers to any dataset with multiple cases or units (such as persons or countries), and multiple observations for each case or unit over time. Traditionally, panel data has been modeled by including intercepts for cases and/or time points to represent the structure of the data. The method usually employed in political science and economics is to use independent intercepts for each time point and/or case, which are called “fixed effects”. In other fields, “varying” intercepts are included that are assumed to be Normally distributed, such as is common in hierarchical/multilevel models. Confusingly, these types of models are referred to as “random effects” in the economics literature. Xu’s paper provides a new framework for thinking about panel data in causal terms, and so is moving beyond these modeling strategies, although it necessarily begins with them.

Xu’s piece, as we would expect, starts with formulas based on the potential outcomes framework. I reproduce his equation 1 here:

This does follow mathematically. But it is a somewhat strange way of presenting this problem because, properly speaking, that is counterfactual inference for a single unit at a single point in time. In other words, this is inherently unknowable as we can only observe one potential outcome for a single time point. The potential outcomes framework, of course, is based on using substitutes for missing potential outcomes. We use a control group to approximate

While I know this seems nitpicky, I think it matters for where we begin when we discuss causal inference in panel data, especially when we start adding in fixed effects and other features of the data. To make matters a bit clearer, let’s return to the classic Rubin formulation for the ATE:

With panel data things get interesting because we are adding in a new dimension of time. We observe now multiple observations for each unit

My point here is simply to say that with panel data we implicitly have two different

This notation should also make it clear what the challenges for inference are with panel data. While many researchers prefer over-time inference, it is clear that we can never obtain randomization of the same nature over time as we can with a cross-section. On the other hand, over-time inference is often considered to be better because it is thought that there is less heterogeneity in the same unit observed over time compared to a cross-section of different units at a given point in time.

As I discuss in my earlier blog post, this folk theorem isn’t necessarily true. It’s easy to imagine situations where over-time inference could be more faulty than a cross-section, especially if the time periods were quite long, such as a panel with hundreds of years. A cross-section would have less heterogeneity in a given year than the same country compared over 300 years apart.

In the limit, it’s of course straightforward to see when over-time inference should be most credible, and that is when

This definition of over-time inference also makes it easier to see what one of the most popular assumptions, sequential ignorability, is all about. In Xu’s formulation, sequential ignorability is similar to his first formula except that he dropped the fixed effects:

Put simply, we are taking an average of over-time observations for each unit

Fixed Effects and DAGs

So far, hopefully, so good. However, potential outcomes alone struggle to answer all causal queries, which is why DAGs have gotten so popular. These diagrams show causal arguments as a collection of variables with arrows pointing in the direction of causality. Intuitive yet very powerful, they can make much clearer what we mean by a causal query.

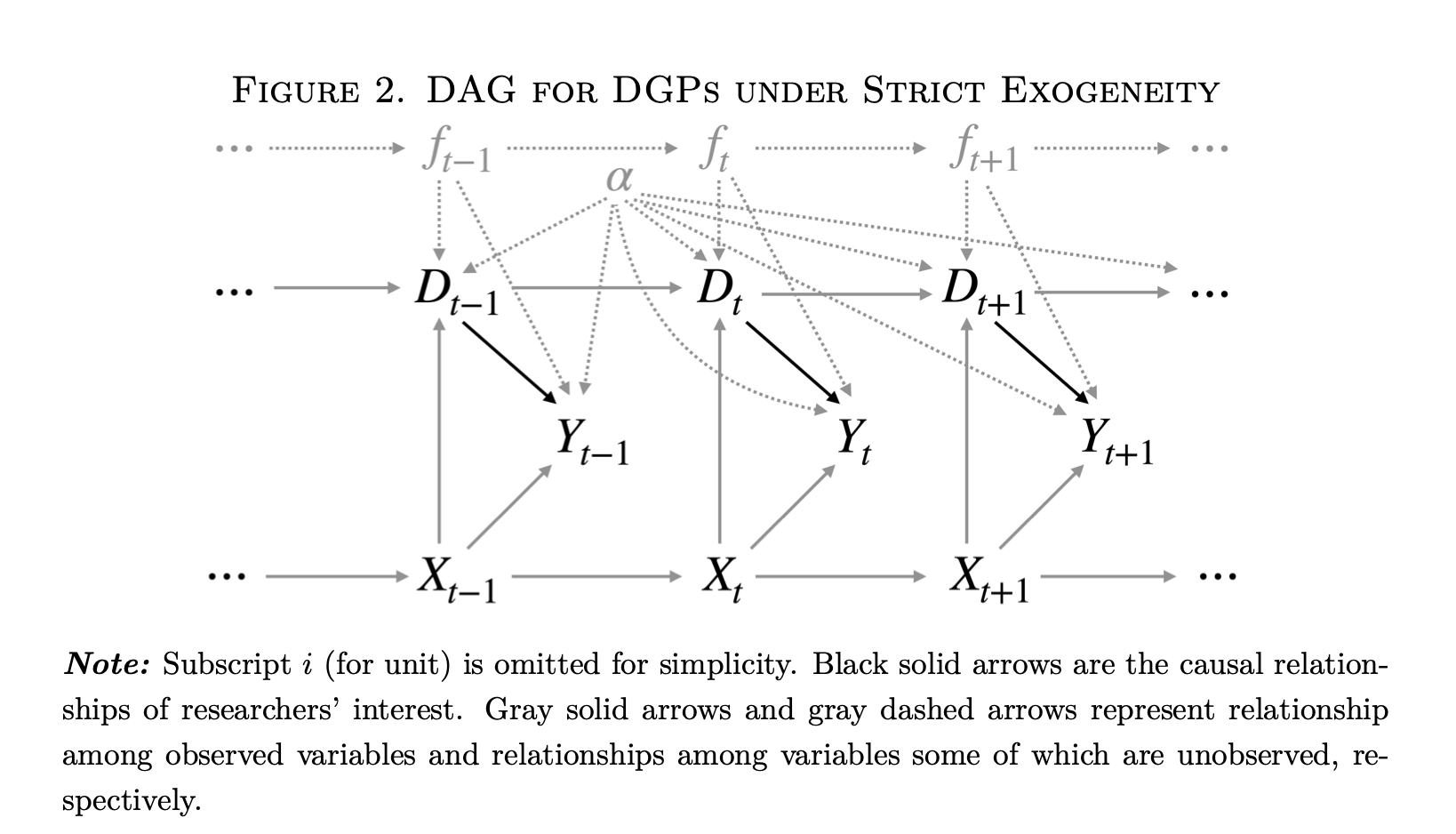

The DAGs are where the limitations of an analysis that ignores the dimensions of variation becomes the most clear. I reproduce below the DAG representing Xu’s “strict exogeneity” (i.e. two-way fixed effects (TWFE) estimation) equation:

This DAG has a lot going on. However, one thing it does not have is a clear indication of the dimensions of variation. We are told simply that this is “panel data.” Which is fine, but–what kind? Looking more closely, we see on the figure caption that “Subscript

However, now we have fixed effects as well in the diagram. For the uninformed, these represent dummy variables or varying intercepts for each time point

This is where things start to get a bit tricky. What are fixed effects and how do we represent them in a causal diagram? Here we are told that they are unobserved confounders. This is a somewhat strange definition. A “fixed effect” is simply a dummy variable for either a case or a time point. It doesn’t in and of itself have any meaning in the sense of a causal factor like income or the presence of COVID-19. In other words, there is an ontological problem in putting fixed effects into a DAG like this because they are substantively different than the other variables, which are more properly real things.

I think this is an important and largely overlooked question in Judea Pearl’s causal diagram analysis: what are the criteria for deciding what is a variable we can manipulate as opposed to just a coefficient from a model without any substantive meaning?

I’ll make the claim that, in a causal diagram, every node on the graph has to be its own separate causal factor. For that to be true, it has to have some kind of independent existence in the “real world.” We could also call it a random variable–some trait we can observe that can take on multiple values. If we have a complete and accurate causal graph, we can then know with confidence which variables we need to measure to ensure so that our statistics have a causal interpretation.

Now going back to Figure 2 above, it’s useful to think about the nodes on this graph and what they mean. The DAG is claiming that the fixed effects

Well… not so fast. Again, one element of causal analysis is that we are studying things “in the real world.” Each element of our graph must be some factor or force or element which we could (at least in theory) manipulate, or apply Pearl’s

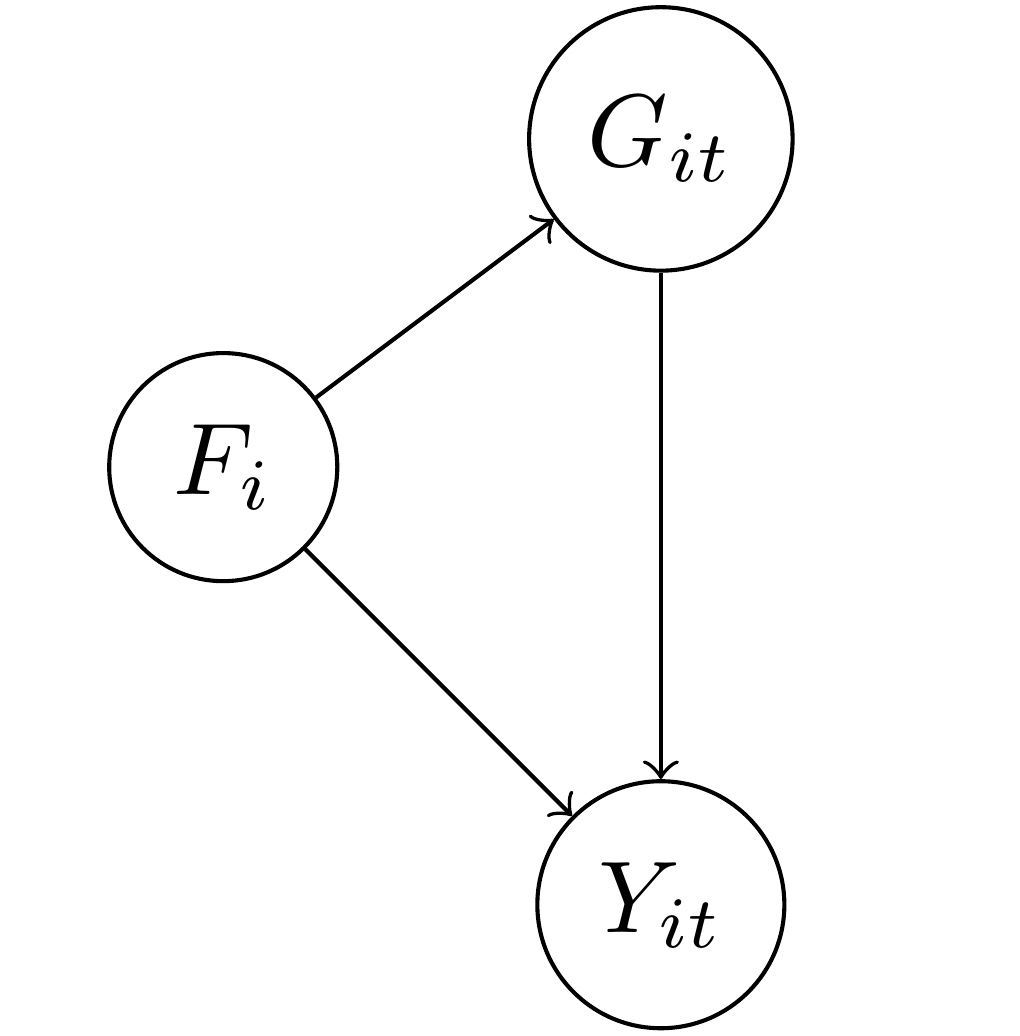

To illustrate this, I’m going to start with a DAG that is much easier to understand and that has an empirical meaning. In this DAG, the outcome

In the diagram I also put

This sort of setup is the typical justification for including fixed effects, or one intercept/dummy variable for each country

Well, I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but including

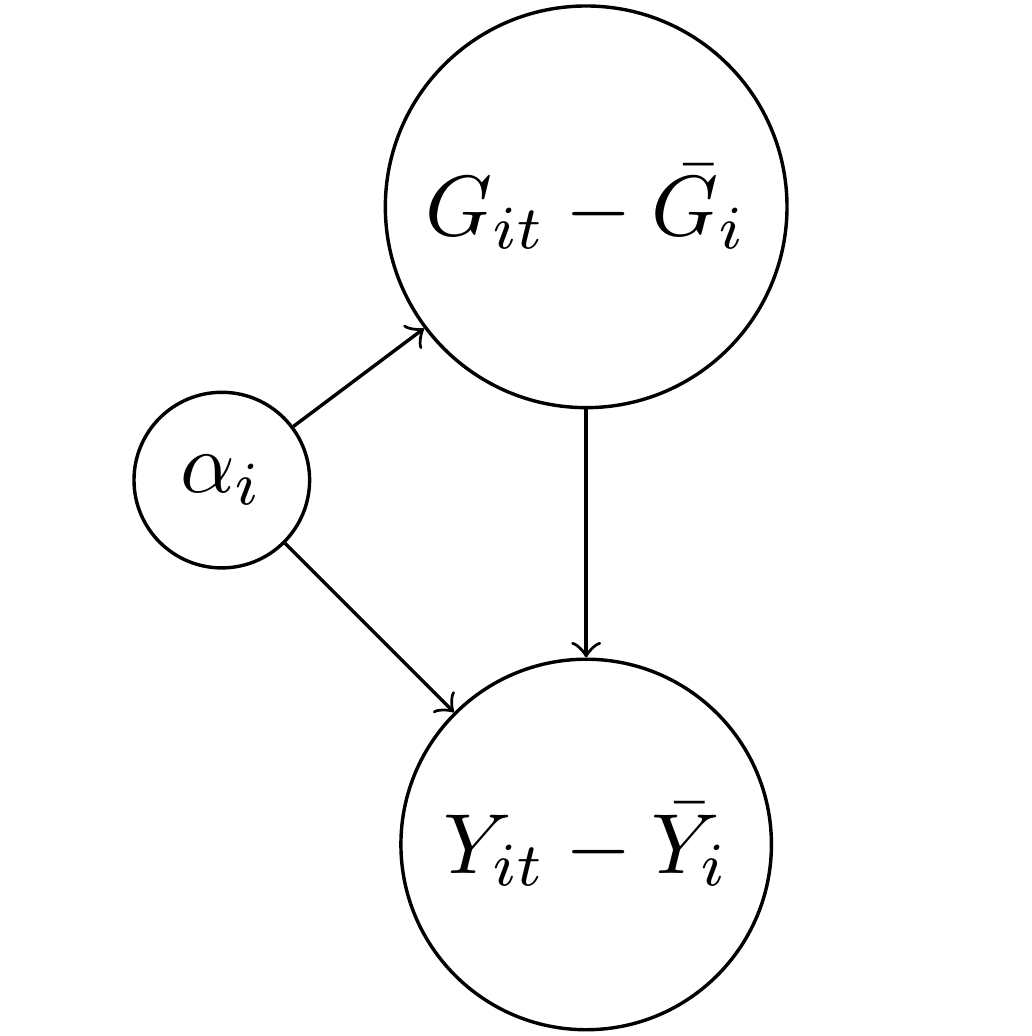

In particular, something happens to the DAG above when we include

The above formula is likely familiar to people who have studied panel data in economics or political science. For both the treatment GDP and the outcome of democracy,

Now did the

However, tornadoes have side effects. We no longer have

So is

If we want to know what the causal effect of

Conclusion

So circling back to the original question… how should we represent fixed effects in a DAG? I don’t think they belong there. Rather, I think we should explicitly show the de-meaning process or notation that signifies it, such as

I discussed this with Yiqing Xu, and he said that the issue can also be framed as having a DAG that also has functional form assumptions baked in. In other words, when we write a DAG, it is supposed to express how random variables are plausibly related to each other–not just specific models. When we start within the framework of a linear model, even one as basic as a panel data fixed effects model, it can be difficult to derive an intellectually-satisfying DAG. Instead, if possible, we want our DAG to represent our substantive knowledge that can subsume various specifications. Granted, this is really, really hard in very general terms, and we probably have more work to do, which is fine. Scholars needs jobs, after all.

Making these distinctions clear can also help clarify more complicated estimators, such as the somewhat infamous new DiD literature. The basic DiD estimand is simply the difference of two cross-section

Finally, there is another way of baking the cake, and that is to try to explicitly estimate a latent confounder rather than rely on intercepts. This is the approach taken by so-called interactive fixed effects models, such as Xu’s other work known as generalized synthetic control, and the matrix completion methods, such as those by Victor Chernozhukov, Susan Athey and Guido Imbens, among others. In this case, the coefficient in a regression model can be given the interpretation of adjusting for latent confounders. The trick with these methods, of course, is how to select the correct form and dimension of this latent variable, and so I think there is more room for work in this area as well.

If you want to read more on the topic of panel data, I have both a prior blog post and a co-authored paper which I recommend you read at your leisure while avoiding tornadoes, miss-specified causal graphs and false equivalencies.